|

Gettysburg 10/04

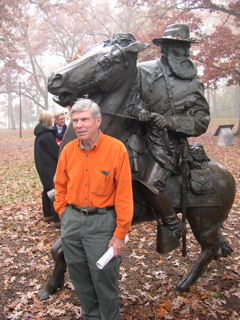

A congenial group of thirty '72 stalwarts, plus assorted spouses, sons, and friends, gathered in Gettysburg, PA at the end of October, for an extended visit to the town and the 1863 battlefield, in the expert company of Prof. James McPherson, recently retired after more than 35 years in Princeton's History Department. On Friday morning Oct. 27th, a number of us traveled with the professor from Princeton in the luxurious motorcoach which would carry all of us around the battlefield for the next three days. (Our group's total headcount was 55 -- exactly the number of seats on the bus). By mid-day most of the rest of us had assembled at the Gettysburg Hotel, having journeyed from the four points of the compass, and from as far as Switzerland and California. At 2 p.m. we headed west out of town, up Seminary Ridge, to our first stop, along the Chambersburg Pike near the McPherson Farm (no relation), scene of the battle's first-day engagement on July 1, 1863 between probing Confederate forces under Gen. James Archer (Princeton 1835) and Gen. Joseph Davis (nephew of Jefferson Davis) and the dismounted Union cavalrymen of John Buford. After an introductory briefing by Prof. McPherson on divisions and brigades, the different varieties of fences, and the damage which solid shot, canister, and grapeshot could do, we learned how additional forces from both sides poured into the fray, that July morning. We consulted the first in our packets of 28 maps, which were invaluable in orienting ourselves and deciphering what happened on the field, hour by hour over the three days of battle. Then we tramped into the woods past the monument to the Union commander, Gen. John Reynolds, killed that morning, and along the route of the Union "Iron Brigade" of Midwestern regiments, which repulsed Archer's Brigade and captured its unfortunate general (who spent most of the rest of the war in Union prisons and died soon after his release). We peered into the railway cut where Yankee gunfire cut down many Confederates, then we headed north to where Ewell's Confederate corps arrived and turned the tide of the day, pushing the Union forces right through the town itself and up onto Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge on the opposite side, where by nightfall the bluecoats were digging in and establishing a formidable defensive position (minus the hapless General Alexander Schimmelfennig, of the Eleventh Corps, who spent the next two days hiding out in a pig-sty). We finished the afternoon at a rarely visited scene of fierce fighting right in town, a few blocks from our hotel. At dinner that evening we rekindled friendships and made new ones. Next morning, we boarded the bus and repeated our ascent up Seminary Ridge, through thick, atmospheric fog, this time turning south and proceeding parallel to the route taken by Confederate Gen. James Longstreet's corps on the battle's second day, July 2, with the goal of attacking the far left of the Union line. Beside the new equestrian statue (1998) of Longstreet, Prof. McPherson recounted the debates which have raged for more than a century about Longstreet's generalship and that of Robert E. Lee, commander of the whole Confederate Army of Northern Virginia (we also debated who looks better on horseback, as depicted in their respective statues). We crossed the Emmitsburg Road and stopped at the Peach Orchard, where another controversial general, New Yorker Daniel Sickles, rashly pushed his corps far out ahead of the Union line, that second day, provoking a rebel attack, and lost his leg to a cannonball in the ensuing fray (and was carried off the field puffing a cigar, so as not to demoralize his men). We hiked across the monument-studded Wheatfield and the forbidding Devil's Den, scene of fierce fighting that day, and climbed Little Round Top to see where Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain's 20th Maine repulsed a series of assaults on the very far left end of the Union line. Michael Shaara's 1974 novel The Killer Angels, along with Ken Burns's 1990 TV documentary and Ted Turner's 1993 Gettysburg movie, together have made this the most visited part of the battlefield. Prof. McPherson gave the valiant Chamberlain and his men their due, but put them in the context of similar heroics by other commanders and regiments fighting shoulder-to-shoulder alongside them. We then moved north along the spine of Cemetery Ridge, following the successive waves of Confederate onslaughts, "en echelon," that second day. Taking advantage of clearer skies, we detoured back to the west of the Emmitsburg Road to climb up a sturdy observation tower for a bird's-eye view of the battlefield. Back on Cemetery Ridge we saw where the First Minnesota Regiment held off a rebel charge for a critical few minutes, suffering ghastly casualties but allowing Union reinforcements time to bolster the line of defense. At the nearby Pennsylvania Monument, as a crew of re-enactors "limbered up" a vintage artillery piece, we took a group photo. Then we moved on to the little-visited northeastern corner of the battlefield, the barb of the fish-hook-shaped Union line: Spangler's Spring, Cemetery Hill, and densely wooded Culp's Hill, where the monuments to Union regiments almost outnumber the tourists. Here, until after sunset on the Second Day, and again in the morning of the Third Day, Ewell's Confederates launched repeated uphill assaults on the entrenched Federals but could not break through. The Union defense here was just as tenacious, and as critically important, as was Chamberlain's on the opposite end of the line, but much less widely known about. At a festive dinner that night, we toasted Prof. McPherson and presented him with a check, in his name, to the Gettysburg National Battlefield Museum Foundation, which will go toward the building of a new Visitors Center (www.gettysburgfoundation.org) On Sunday morning, under bright sun and blue sky, we tramped two battlefields of the Third Day, July 3, one of them hardly visited at all -- the East Cavalry Field, where Jeb Stuart's Confederate horsemen, arriving late to the battle, crossed sabers and carbines with the Union troopers of George Armstrong Custer, and were repulsed -- and the other, probably the best known, the scene of Pickett's Charge (more accurately known as the Pickett/Pettigrew advance, as we learned). There we assembled at the Virginia Monument on Seminary Ridge, where Lee himself surveyed the attack, and followed the route of the rebel advance, east across the fields and fences toward the stone walls and clumps of trees which marked the Union line. Crossing the Emmitsburg Road and reaching the "high-water mark" of the Confederate advance, we heard how the attack was broken and repulsed, including the controversy about where the 72nd Pennsylvania Regiment's monument deserved to be located, which was only settled in a postwar courtroom. We saw the newest monument, to a Mississippi regiment (thank you, Trent Lott), and finished the morning at the nearby National Cemetery, where Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address four months after the battle. Our visit ended at Sunday noon, and we all returned home wiser about our history, inspired by how it is taught by the likes of Prof. McPherson, sobered by the close contact we had with the national tragedy of the Civil War, and buoyed by the fellowship of classmates and their families.

|

|